People at Work in the EEA

ESA, EFTA Court Conference in Brussels, 14 June 2019

When the Althingi, Iceland’s parliament, passed legislation implementing the Agreement on the European Economic Area in early January 1993, I was chairman of its Foreign Affairs Committee, which held a total of 82 meetings on the subject.

When Iceland became a member of EFTA in 1970, however, there were only two meetings of the Foreign Affairs Committee on that subject, which was actually Iceland’s first step into an international free market economy.

The number of meetings we held in 1992 of course reflected the depth of the disagreement on participation in the EEA Agreement. However, this disagreement quickly evaporated, and in 2007 a committee of all the parliamentary parties, where I was chairman, returned an opinion confirming the full support of all the parties for membership.

This last winter an acrimonious dispute suddenly surfaced in Icelandic politics relating to the EEA membership because of the implementation of the directives and regulations forming what is known as the Third Energy Package. The dispute is still being dealt with in the Althingi.

This dispute prompted about 270 people, young people, to join forces on a full-spread advertisement under the heading: “Don’t gamble with our future.” It also said “We support Iceland’s continued membership of the EEA Agreement. We want a free, open and international society and we stand united against isolationism.”

The phrasing reflects greater polarisation on any EEA issue than has been seen in Iceland for 25 years, a polarisation that also manifested itself, for example, in the recent elections to the European Parliament. In that case, however, young people offset the wave of opposition to multinational co-operation by lending their support to green parties.

We have to take note of these trends when discussing the subject of People at Work in Europe. In many countries, the opening up of the labour market and free movement of people have given rise to doubts about the EEA co-operation.

The best way to ensure the success of co-operation in the EEA is to remind each and every citizen in our respective countries how much the participation means to him or her personally. Everyone has the same rights, but people exercise these rights in different ways, not least because of their different jobs.

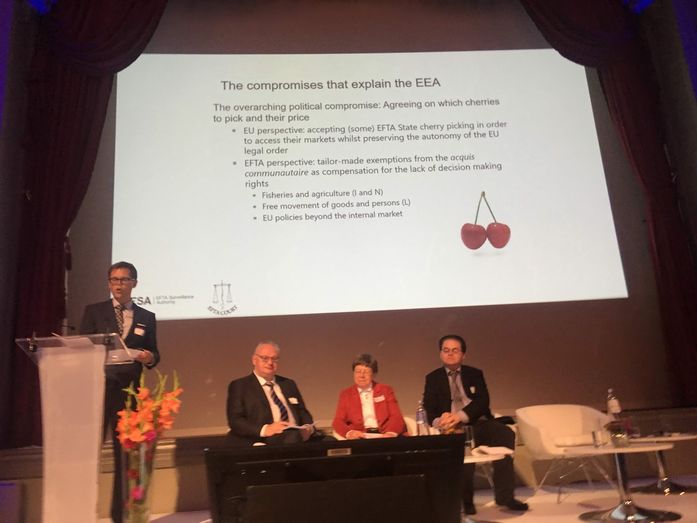

Myndina tók ég á ráðstefnunni í Brussel 14. júní 2019 Í ræðustól er prófesor Halvard Haukeland Fredriksen við Háskólann í Bergen. Frá vinstri sitja Páll Hreinsson, forseti EFTA-dómstólsins, Eleanor Sharpston, yfirlögfræðingur frá ESB-dómstólnum, og Steve Peers, prófessor við Essex-háskóla.

Myndina tók ég á ráðstefnunni í Brussel 14. júní 2019 Í ræðustól er prófesor Halvard Haukeland Fredriksen við Háskólann í Bergen. Frá vinstri sitja Páll Hreinsson, forseti EFTA-dómstólsins, Eleanor Sharpston, yfirlögfræðingur frá ESB-dómstólnum, og Steve Peers, prófessor við Essex-háskóla.

In the majority opinion of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Althingi of 30 November 1992, the element of the four freedoms relating to free movement of persons is phrased to the effect that the citizens of each Contracting State are free to travel to other Contracting States and remain there for up to three months while seeking employment, and if employment is found within that time they will be issued a residence permit, effective for a term of five years with automatic renewal.

This simple text led to a revolutionary change, particularly after the enlargement of the European Economic Area eastwards. In the EEA Agreement the text remains unaltered from its original wording of 25 years ago. However, the concept of the free movement of persons has changed in meaning. The Treaty of Maastricht of 1992 introduced the notion of EU citizenship to be enjoyed automatically by every national of a Member State.

This means that each citizen of the EU, with spouse and family, has the right to free movement and residence in the territories of the Member States. This EU legislation has been adapted to the EEA/EFTA states. EEA law now refer to EEA citizens. What is remarkable is how quietly this change in the legal status of individuals has occurred.

The work environment changed in so many respects in Iceland with the membership of the EEA that in reality the change amounts to a social revolution. In particular, the change affected the educated classes, universities and the research and scientific community. Participation in the European educational and cultural programmes that came with the membership of the EEA created an entirely new dimension in Icelandic society. Tens of thousands of Icelandic students have benefited from this participation, which in many cases has had a significant impact on their choice of career following completion of studies. The impact on the labour market is therefore both direct and indirect. This dimension is now taken for granted, and perhaps it is for many a distant memory, or altogether unknown, how it came about and thanks to what.

However, recently an Icelandic architect, Hilmar Thor Björnsson, published on Facebook his own experience of the membership.

He says that the Agreement changed “just about everything”, that it resulted in “a transformation of the working environment and opportunities of architects”. Competition increased and architecture improved. “This was a milestone that many people do not apprehend and no doubt many have forgotten,” he says.

This reminds us that what before was a watershed is now taken for granted. Some of the doubts about the importance of the EEA in our daily working life merely confirm that the Agreement is a victim of its own success.

Let us look at the changes in Iceland that can be traced to the enlargement of the European Union to the east.

The number of foreign nationals in Iceland has grown by 67.6% in three years since 2015. By the end of 2018 they were 44,000, about 12.4% of the population. Most of the foreign nationals are Poles, at about 19,000, followed by Lithuanians, at about 4,000.

Twenty-five years ago, no one could have foreseen that Eastern Europeans would play such an important role in the Icelandic economy.

The construction industry and tourism would be a shadow of themselves without them.

In spite of this development immigration matters have not been a prominent issue in Icelandic politics. The country’s infrastructure, geared to the slow-paced growth of a nation of 340,000 people, has been able to handle this load, in addition to up to 2.5 million tourists a year.

The labour market is changing. The distinction is diminishing between the traditional relationship of workers with employers and contracting and self-employment This is particularly a result of technological advances and temporary assignments where commercial activities fluctuate.. Under these conditions foreign nationals are at particular risk of being marginalised.

This trend is increasingly influencing the attitude of labour unions to the EEA Agreement.

The business activities of temporary work agencies and posted workers are a cause for concern, new national legislation on temporary work agencies and posted workers has been passed.

Yesterday [13 June] the Council of the European Union adopted a regulation establishing a European Labour Authority (ELA), which deals with labour mobility and social security coordination.

It has been pointed out that the rules may be adequate, but that monitoring, disclosure of information and follow-up mechanisms are lacking The role of the European Labour Authority is to report cases of undeclared work, violations of working conditions or labour exploitation and cooperate with the member states in order to solve cross-border disputes on matters relating to the labour market.

It is necessary to tread carefully in this regard. In the spring of 2018, the EU issued a new directive on posted workers. Views regarding the directive are polarised, primarily between countries in the west and the east, as the EU states in eastern Europe have created for themselves a competitive advantage based on their ability to offer postings in a cheap manner.

The Icelandic labour movement has steadfastly supported Iceland’s membership of the EEA. The movement has been a very active participant in the collaboration of European labour unions, and resolutions have been passed at conferences of the Icelandic Confederation of Labour to the effect that Iceland should co-operate closely with the EU, and even apply for membership of the Union.

The current leaders of the Icelandic Confederation of Labour are more critical in this regard than their predecessors. This has, among other things, been manifested in the discussion of the Third Energy Package. Viewpoints have emerged that would have been unthinkable just months ago. Now there are warnings of a growing marketisation in the EEA, that electricity should be under public control and not a product in the marketplace. It is argued that too many steps have been taken already in the direction of marketisation of the basic pillars of society, and that its further expansion would be a dangerous route to take.

The phrasing shows that the opposition is not only to the Third Energy Package, but in fact to the main pillars of the internal market and thereby the membership of the EEA.

This political trend has to be aired and discussed. We are dealing here with the fact that membership of the EEA does not hold the same promise of change as it did at the outset. Many things are more politically exciting than praising the benefits of the EEA. Still, this has to be done and the defence of the EEA needs to be organised like any other task.

In that defence, the rights of the individual should play a prominent role, rights that have been created and shaped by the laws and rules in the European Economic Area. International co-operation creates new individual rights. Those cross-border rights have no national boundaries. Locally they may, on the other hand, challenge some deep-rooted structural forces.

The EEA Agreement provides for the right of individuals. People at work in the European Economic Area should enjoy this important right.

Ladies and gentlemen!

This brings me to the end of my address. We have before us a scenario of social changes which are of such a magnitude that there will be no turning back without grossly violating the rights of those that are benefiting from the changes. However, ensuring that these changes do not imperil the core of our societies, our culture and national aspirations, is a heavy responsibility. The goal is not to cast everyone in the same mould, but to give everyone the opportunity to fulfil their life’s ambitions in employment of their choice as free citizens.