Iceland and the EEA - í norskri skýrslu

Fylgiskjal með norskri skýrslu um EES-samstarfið sem birtist 11. apríl 2024.

Norska ríkisstjórnin skipaði í maí 2022 nefnd til að meta reynslu Norðmanna af EES-samningnum og öðrum samningum Norðmanna við ESB undanfarin 10 ár. Skýrslan var birt 11. apríl 2024.

Hér má nálgast skýrsluna í pdf. útgáfu.

Með skýrslunni eru viðaukar sem aðeins birtast sem fylgiskjöl á netinu og þar á meðal er þessi grein um Ísland og EES en ritun hennar lauk í febrúar 2024.

Espen Barth Eide, utanríkisráðherra Noregs, hampar EES-skýrslunni eftir að hafa tekið við henni frá Line Eldring, formanni EES-nefndarinnar.

Summary:

- EEA Membership and Benefits: Iceland's membership in the European Economic Area (EEA) based on common rules and equal conditions for competition has yielded significant benefits, including access to European markets, more flexible and versatile labour market, innovation, and competitiveness. It has also facilitated the free movement of people, fostered diversity, and addressed societal challenges. Additionally, participation in EU Framework Programmes for Research and Innovation and the Erasmus program has enhanced research capabilities and educational opportunities in Iceland.

- Challenges and Adaptations: While EEA membership has brought advantages, it has also presented challenges. Adapting to EU regulations, ensuring fair competition, and integrating migrants into Icelandic society have required reassessment and effective policy-setting. Specific and important adaptations have been successfully negotiated in areas such as aviation security, energy performance, and fishing industry regulations.

- Legal and Constitutional Issues: There has been some debate regarding the compatibility of EEA membership with the Icelandic Constitution. Prevailing legal opinions have concluded that membership does not contravene the Constitution, but discussions have arisen concerning the transfer of sovereign powers to international organizations.

- Alternatives and Conclusion: Alternatives to EEA membership focus on negotiating free trade agreements and relying on EFTA membership. However, the report concludes that the EEA membership has been the most successful trade solution for Iceland, leading to prosperity and opportunities. Remaining in the EEA is seen as the most advantageous option based on the past 30 years of experience.

Overall, the report highlights the benefits, challenges, legal considerations, and alternative options related to Iceland's membership in the EEA, ultimately emphasizing the success and importance of the EEA arrangement for Iceland's trade and economic prosperity.

1. Background on Iceland's Relations with the EU

Icelandic political debate has been dominated by disputes over Iceland's participation in international cooperation for decades. In the early days of the Republic of Iceland, founded on June 17, 1944, controversies surrounding measures to ensure national security and defence left a strong mark on internal politics. When Alþingi (the Icelandic parliament) voted on Iceland joining NATO as a founding member in 1949, clashes occurred between the police and protesters opposing the membership. Two years later, in 1951, Iceland and the United States entered into a bilateral defence agreement, which was less politically controversial than the NATO membership.

Today, all Icelandic political parties support a national security policy adopted by Alþingi. The fundamental premise of the policy is Iceland's position as a nation with no military that ensures its security and defence through active co-operation with other states and within international organisations. An emphasis is laid on NATO membership as a key pillar in Iceland´s defence and the US/Icelandic bilateral agreement of 1951.

Iceland prepared to join the European Economic Community (EEC) between 1961 and 1963. However, when General Charles de Gaulle, President of France, vetoed the UK's bid to join the EEC, discussions on Iceland's membership came to a halt.

Between 1962 and 1966, the Icelandic economy experienced rapid expansion, and Icelanders were therefore unaware of the economic disadvantages of not being part of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) or the EEC.

In 1967, the Icelandic economy took a downturn. In 1968, there were plans to establish NORDEK, a Nordic economic organization similar to the EEC. A treaty was negotiated to have NORDEK headquartered in Malmö, Sweden. However, Finland did not ratify the treaty due to its relationship with the Soviet Union.

Once NORDEK was off the table, Alþingi authorized the government to apply for membership in EFTA. Negotiations with the free trade association began in January 1969, and Iceland became an EFTA member on March 1, 1970.

Iceland, therefore, became a belated participant in European economic cooperation, as it had a strongly regulated economy until 1959 when the coalition government of the Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur), a centre-right party, and the Social Democratic Party (Alþýðuflokkur) was formed. This coalition remained in power until 1971.

When Iceland's membership in EFTA was being considered in Alþingi, the People's Alliance (Alþýðubandalag), a far-left party, turned against it, while members of the Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkur), a liberal party, abstained from the vote. In 1971, these parties formed a coalition with a social democratic splinter group. This government completed Iceland's free trade agreement with the European Community, which came into force after unanimous adoption by Alþingi in 1973.

During the free trade negotiations, EC negotiators, for the first time, demanded that Iceland grant fishing permits for EC vessels in the Icelandic fisheries jurisdiction in exchange for tariff concessions for fish products on the EC market. Iceland consistently rejected this demand.

In 1972, Iceland extended its fisheries jurisdiction from 12 to 50 nautical miles, and in 1975, from 50 to 200 miles. Both extensions led to conflicts between the Icelandic Coast Guard and the British Navy (Cod Wars) before agreements were eventually reached. In 1982, when the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted, Iceland's sovereignty over the 200-mile exclusive economic zone (about 750,000 square kilometres) became internationally recognized.

In 1985, the European Community decided to establish a European internal market, effective from January 1, 1993, which necessitated a re-evaluation of EC and EFTA cooperation. Negotiations began, resulting in the agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA).

After elections in 1991, the Independence Party and the Social Democratic Party formed a coalition, enabling the signing of the EEA Agreement on May 2, 1992. The issue sparked a major political debate in Alþingi. The governing parties argued that EEA membership would serve Icelandic interests better than joining the EC, and the government decided not to apply for EC membership.

On December 6, 1992, the Swiss voted "no" to joining the EEA in a referendum, with 50.3% voting against and 49.7% voting in favour. Following this result, EC accession was no longer considered by Switzerland.

In the debate in Iceland, there were demands for a referendum on EEA membership, but the government rejected them. Icelanders might have faced a situation like Switzerland if the nation had been consulted.

Alþingi voted in favour of EEA membership on January 12, 1993, with a resolution passing by 33 votes to 23, with seven abstentions.

In the summer of 2004, the Prime Minister appointed a committee representing all parliamentary groups to consider Iceland's relations with the European Union. In March 2007, the committee unanimously concluded that the EEA Agreement had stood the test of time and that it would be appropriate to further develop the agreement as it formed the very basis of relations between Iceland and the EU.

The conclusion reached by all parties regarding EEA membership marked a historic moment of harmony. While all parties supported EEA membership, individual representatives expressed differing views on EU membership. The Social Democratic Alliance (Samfylking successor to Alþýðuflokkurinn) showed favour towards EU membership, emphasizing the desire to fully participate in European cooperation. The Progressive Party, at the time in a coalition with the Independence Party since 1995, also expressed an interest in exploring EU membership. On the other hand, opponents of EU membership were represented by the Independence Party and the Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin – grænt framboð successor to Alþýðubandalag). These different positions displaced the range of perspectives within Icelandic politics on the topic of EU membership.

Following parliamentary elections in the spring of 2007 the Progressive Party left the coalition with the Independence Party which joined the Social Democratic Alliance for the first and only time until now in government. This led to a more positive policy towards the EU with a social democratic foreign minister keen on exploring how Iceland's interests would be best served in relation to the European Union (EU). However, after the collapse of Icelandic banks in 2008, pressure from the Social Democratic Alliance to explore EU membership increased. In January 2009, it became apparent that most members of the Independence Party were opposed to EU membership. Subsequently, the Social Democratic Alliance left the coalition, and a minority left-wing government was formed on February 1, 2009, by the Social Democratic Alliance and the Left-Green Movement, with support from the Progressive Party.

After parliamentary elections in spring 2009, the country formed its first "pure" left-wing government with a majority from the Left-Green Movement and the Social Democratic Alliance. The government's policy towards the EU involved proposing an application to join the EU to Alþingi.

The government expressed support for EU membership, albeit with reservations concerning Iceland's interests in areas such as fisheries, agriculture, regional and currency matters, environmental and natural resource matters, and public services. The governmental parties agreed to respect each other's differences on EU membership and their right to openly debate and promote their viewpoints, drawing parallels with Norway's approach at the time.

The application process began on July 17, 2009, following the approval of the foreign minister's proposal by Alþingi the day before by 33 votes to 28, with two abstentions.

Hopes were initially high for a swift negotiation process, with expectations of concluding accession negotiations within 18 months or even less, based on the experience of the EU's negotiations with EFTA states in the early 1990s. However, no clear time frame for Iceland's accession was set by the EU, unlike the case with the EFTA states after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 2006, the EU had implemented a new enlargement policy, which was applicable to Iceland in 2009. This policy included specific opening and closing benchmarks for accession negotiations. These benchmarks allowed any EU member state to oppose the start or conclusion of negotiations on any policy area unless their conditions were accepted, even if the conditions were unrelated to the specific policy area. This gave any EU member state the power to obstruct Iceland's EU application.

Iceland's primary concerns during the negotiation process were related to agriculture and fisheries. The negotiation chapter on agriculture was never opened, and the chapter on fisheries reached a halt before the screening report could be concluded and negotiations initiated. The benchmarks proposed by the EU for opening the fisheries chapter were unacceptable to Iceland.

Furthermore, the Netherlands, during the summer of 2010, declared that they would delay Iceland's accession unless the so-called Icesave dispute, which arose after the 2008 banking crisis, was resolved according to their demands. The Icesave dispute with the Netherlands and Great Britain was eventually resolved in favour of Iceland by the EFTA Court on January 28, 2013.

Iceland's foreign minister decided in January 2013 to suspend the EU accession negotiations and reassess the situation. Parliamentary elections were held in the spring of 2013, and the government parties suffered significant losses. Since then, EU accession has not been on the agenda of any subsequent government.

All political parties in Iceland agree that the Icelandic Constitution needs to be amended to include a provision regarding the transfer of sovereign powers before EU accession can take place. There is also consensus among the political parties that a referendum is necessary to obtain a mandate for a renewed EU application.

(For reference material on EU accession negotiations, you can consult "Viðauki I: Aðildarumsókn Íslands og stækkunarstefna ESB" by Ágúst Þór Árnason, Faculty of Law, University of Akureyri, and "Úttekt á stöðu aðildarviðræðna Íslands við Evrópusambandið og þróun sambandsins" by the Institute of Economic Studies at the University of Iceland (2014).)

2. Iceland's EEA Membership in the Past Decade

In 2018, the foreign minister received a request from 13 members of Alþingi to provide a report on the pros and cons of Iceland's membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), as well as the impact of the EEA agreement on Iceland.

The parliamentarians believed it was important to objectively evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of European cooperation, considering the practical experience Iceland had gained thus far. They also emphasized the need to shed light on the imminent challenges, particularly with the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union and its potential impact on the EEA Agreement.

The request also referred to a report commissioned by Norway on its EEA membership, which was prepared by experts and published in 2012. The parliamentarians highlighted the serious questions raised about the democratic deficit and loss of sovereignty resulting from Norway's participation in the EEA Agreement and the Schengen cooperation. They pointed out that the EEA Agreement had influenced a broader range of social dimensions than originally intended in 1992. Ongoing debates in Norway regarding a legislative bill on the country's participation in EU energy legislation further emphasized the need for assessment.

Consequently, the parliamentarians concluded that it was crucial to conduct a similar assessment of the consequences and functioning of the EEA Agreement in Iceland. They emphasized that as the EEA Agreement had been in force for 25 years by the end of that year, a comprehensive review of its impact was timely, especially as Iceland was celebrating 100 years of sovereignty.

The request for the report specifically mentioned the discussion and debate surrounding what was referred to in Iceland as the "third energy package" (ACER in Norway), which Alþingi adopted with 46 votes in favour and 13 against on September 2, 2019. However, it was evident that there were other motives behind the request, as reflected in the desire for a comprehensive review of the effects and functioning of the EEA Agreement in Iceland.

In response to the request, the foreign minister appointed a three-person working group on August 30, 2018, and provided them with the following terms of reference:

- Summarizing and assessing the benefits Iceland has enjoyed through participation in EEA cooperation and identifying the principal challenges faced by the government in implementing the EEA Agreement.

- Assessing the legal framework implemented into national law in the areas covered by the EEA Agreement and analysing the business, economic, political, and democratic implications.

- Surveying developments in relations between the EEA EFTA states and the EU, considering any changes resulting from the United Kingdom's exit from the EU and examining the status of the EU-Switzerland relationship.

- Taking into consideration reports issued in recent years on Iceland's relations with the European Union, including the comprehensive report prepared by Norway six years ago regarding Norway's relations with the EU.

- Compiling a list of references and academic literature related to Iceland's membership of the EEA Agreement.

The working group submitted its 301-page report in September 2019, aiming to provide a historical context for Iceland's membership in the EEA and the development of international financial and economic cooperation since the end of World War II. The report explains the scope of the Agreement, the procedures for amending its Annexes, and examines internal procedures in relation to the Agreement. It outlines the policy areas covered by the Agreement and describes its institutional framework.

Additionally, the report provided an account of all legislation directly relevant to the EEA that Alþingi has adopted from 1992 until September 2, 2019. The Prime Minister's Office and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs authorized the working group to publish a report including summaries of constitutional opinions regarding EEA membership. The publication of these opinions reinforced the validity of the report and ensured consistency and accuracy in handling this delicate aspect.

In summary, everyone interviewed by the working group expressed the opinion that the EEA Agreement is alive and well, conferring significant benefits for those operating within its framework. This however did not include the representatives of "Frjálst land" in Iceland and "Nei til EU" in Norway,

The foreword of the report states that Icelandic society has been transformed through its accession to the EEA. However, conducting a comprehensive review of the development of Icelandic society from the past to the present would require extensive resources and time. Moreover, it is doubtful that reverting to the past would serve any purpose, considering the radical changes described in the report.

Icelandic society was transformed through its accession to the EEA. The participation in the European funding programmes for research and innovation laid the ground for a new and steadily growing dimension, which has affected both higher education and industry. Some studies have been conducted on the economic impact of the EEA membership, but they are incomplete, as it is impossible to cover all aspects of the trends. However, one can find them here: Iceland Economic Growth 1960-2023 | MacroTrends. Iceland Economic Growth 1960-2023 | MacroTrends

Engaging in a comparison of what was and what is now would require a very comprehensive review of the development of Icelandic society, as the changes have been so profound. It is, in fact, doubtful that reverting some 30 years would serve any purpose, bearing in mind the societal transformations in the last decades. However, the Agreement has developed and has proven to be resilient alongside these societal changes and progress in the internal market.

The working group's objective was not to pass judgment on the pros and cons of EEA cooperation, but rather to present the facts and allow the readers of the report to form their own opinions.

The working group identified fifteen points for improvement, as follows:

- It is recognized that there has been no comparable opportunity since 1992 for a trade and cooperation agreement with the EU that could replace Iceland's EEA membership. Doubts about the compatibility of EEA membership with the Icelandic Constitution weaken Iceland's position vis-à-vis partner countries, particularly Norway and Liechtenstein.

- The ongoing constitutional debate regarding EEA membership must be concluded, either by recognizing the constitutional status of this membership, like other unwritten constitutional rules, or by amending the Constitution to explicitly address Iceland's membership in the Agreement.

- It is essential to actively recognize that EEA membership has shaped Icelandic society, rather than perceiving it as foreign encroachment on national sovereignty. Integration should be acknowledged as an integral part of independent international cooperation, with sovereign states having the freedom to define their trajectory in this regard.

- Under the EEA Agreement, the Icelandic government can make independent decisions and defend Iceland's interests. If there is a desire to expand this scope, any changes should be jointly introduced by the EEA/EFTA states, as the EU will not initiate amendments to the EEA Agreement.

- The EEA/EFTA states should aim to strengthen the two-pillar structure and ensure the credibility of its institutions. The EFTA pillar must remain robust for the structure to thrive. Attention should be given to reinforcing the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) due to increased specialization in cooperation with EU agencies.

- Delegation of decision-making power from the European Commission to EU agencies provides the EEA/EFTA states with more influence in decision-making than they previously had. The EU agencies and their functions should be seen as opportunities rather than threats for the EEA/EFTA states.

- If Iceland were not aligned legislatively with the EEA and operated under its own rules, there would be a significant risk of isolation, stagnation, and regression across all sectors of society. This is particularly true for the economy and industrial activities, which have been greatly impacted by technological advances. The Translation Centre of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs plays a vital role in facilitating neologism and translation in this context.

- In the EEA, there is a conflict between states in the North and South, particularly concerning labour unions and workers' rights. To safeguard institutions of general economic significance and core values of Icelandic society, Nordic legal cooperation should be initiated to have a greater say in shaping EU legislation. Inge Lorange Backer's 2018 report for the Nordic Council of Ministers contains valuable proposals in this regard.

- Responsibility for EEA matters within the national administration should be determined through a presidential decree allocating functions between ministers. It should be recognized that EEA cooperation is largely a domestic affair, and the role of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs should be defined accordingly.

- The governance and conduct of EEA affairs internally should be further solidified. An administrative coordination centre for EEA affairs should be established within the national administration, staffed with permanent officers who continuously monitor policy matters during the decision-making and implementation stages.

- The government's list of priorities for important EEA matters should be pursued decisively. These matters should be given greater priority within ministries, with specialist staff and political criteria informing decision-making. Experience shows that the EEA/EFTA states can achieve considerable success in advancing their interests through factual arguments.

- A human resource policy should be formulated to support government participation in EEA cooperation. Those involved in this work should have opportunities to acquire specialized knowledge through study and research leaves at foreign universities, academic or research institutes.

- EEA research activities should be promoted across various disciplines, not limited to law. An EEA think tank should be established through cooperation between the government, stakeholders, and research institutes to serve in an advisory capacity, facilitate public debate, and organize seminars.

- Politicians, ministers, and parliamentarians should devote more attention to EEA matters, as their participation is crucial in communicating Iceland's political viewpoints. Alþingi should maintain a liaison officer post in Brussels to foster relations with the European Parliament.

- Over the years, tens of thousands of Icelanders have benefited from the rights conferred by EEA participation, such as the right to seek education or medical assistance in other countries. Balancing rights, obligations, and benefits has been and remains a principal objective of EEA cooperation, and the Icelandic government should duly consider this.

In general, the report garnered positive reception across various domains, with several proposals being implemented to varying degrees, and ongoing advancements adhering to the direction and essence of others.

Concerning points 1 and 2 related to the constitution, the necessity to address disputes regarding Iceland's sovereignty status is acknowledged within the constitution review process. It is pertinent to note that the ultimate phrasing of these proposals may spark contention, especially if they imply a transfer of powers to the EU.

When the current government was established in late November 2021, the Presidential Decree, assigning tasks to ministries, delegated EEA-related matters exclusively to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). Nonetheless, the Prime Minister's Office has gradually been involved in coordinating European affairs, as affirmed in the decree, and is currently doing so in collaboration with the MFA. The proposal aims to further consolidate the governance and management of EEA affairs within Iceland. One suggestion is to create an administrative coordination centre for EEA affairs within the national administration, staffed by permanent officers overseeing ongoing monitoring throughout policy development and implementation phases.

Progress towards this objective is being made gradually. The Icelandic permanent delegation in Brussels, which includes representatives from all relevant ministries, is crucial in implementing the government's prioritized initiatives. It works in close conjunction with the Directorate for External Trade and Economic Affairs in the MFA. Additional emphasis is being placed on human resources management in the realm of EEA Affairs.

Although the proposal to establish an EEA think tank has not come to fruition, initiatives to bolster communication among EEA stakeholders, politicians, ministers, and parliamentarians are in progress. Within this context, the importance of the EFTA Parliamentary Committee cannot be overstated. Furthermore, there is a keen interest within the Alþingi to foster relations with the EU Parliament by sustaining a liaison officer position in Brussels.

None of the proposed practical measures or their foundational objectives are intrinsically contentious, although the prioritization of some implementations may have been lacking.

Regarding point 5 about the two-pilar system it must be kept in mind that this structure serves as the cornerstone of EEA cooperation. Within the EEA framework, none of the EEA/EFTA countries are willing to relinquish their sovereign decision-making powers to the EU without becoming full members of the Union. The two-pillar arrangement ensures that no binding decisions are made without the direct involvement of representatives from the three EEA/EFTA countries in the European Surveillance Authority (ESA) and the EFTA Court.

Participating in EEA cooperation necessitates that nations continually adapt to rapid and ongoing changes, making legally binding decisions accordingly. The pressure on the two-pillar structure intensifies as an increasing number of intricate rules and regulations are implemented with more complex oversight mechanisms.

The introduction of specialized agencies has placed new demands on ESA, as it serves as the representative of the EEA/EFTA countries, authorized to make binding decisions on behalf of the EFTA countries. These decisions are made in consultation with and based on drafts from the relevant EU agencies. Notable examples include the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA), and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA). A similar approach has been taken regarding ACER and the third energy package. This trend raises questions about the need for enhanced specialized expertise within ESA to be on par with their EU counterparts.

The EFTA Court has gained significant respect on the EU side, further solidifying the importance of the EFTA pillar in the two-pillar structure. It is in the best interest of the EEA/EFTA countries to ensure the high standing and credibility of this court.

For the effective functioning of EEA cooperation within the EEA/EFTA countries, maintaining the strong reputation of both ESA and the EFTA Court is of paramount importance. The institutions must also be afforded with the necessary resources so the EFTA pillar can function properly.

In point 6 it is stated the EU agencies, and their functions should be seen as opportunities rather than threats for the EEA/EFTA states. Three examples can be mentioned to support this statement:

MAST, the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority, serves as both the national European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Focal Point and the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) Contact Point. Additionally, MAST represents Iceland at the Management Board and the Advisory Forum of the EFSA, playing a important role by being appointed as EFSA's Focal Point and RASFF Contact Point.

MAST's participation in the Management Board is crucial, enabling it to exert direct influence over EFSA's work. Without this level of access and the ability to engage in open, active discussions, Iceland would be isolated in this domain.

It is noteworthy that Iceland, as one of the few major fishery nations involved in the EFSA, plays a key role in ensuring that fishery and maritime interests are represented. Given that agricultural concerns often dominate deliberations, it is vital, from both an Icelandic and, likely, a Norwegian perspective, that these interests are adequately represented on the Management Board and other instances within EFSA.

The Icelandic Data Protection Authority (IDPA) plays a proactive role in the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). Either the director of the IDPA or their representative engages in board meetings, ensuring that Iceland's perspectives are voiced, and proposals are presented in discussions that aim for consensus without necessitating a vote. Despite an extensive array of sub-committees within this domain, attendance at all meetings or the undertaking of specific tasks is not always feasible for Iceland, owing to a demanding workload domestically. Nonetheless, representatives from the IDPA have been instrumental in shaping rules within specific data protection arenas.

Similarly, the Icelandic Medicines Agency (IMA) maintains a robust collaboration with the European Medicines Agency (EMA). With the Icelandic director actively participating on the EMA board and IMA representatives contributing to numerous sub-committees within this sector, the guiding principle mirrors that of the EDPB and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA): the value of professional contribution supersedes nationality.

3. The Administrative Structure

The administrative structure for EEA affairs in Iceland involves various government bodies and coordination mechanisms. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) have central roles in coordinating EEA matters. Each ministry in Iceland is responsible for EEA issues within its specific portfolio.

At the MFA, the European Department, headed by the Deputy Director General for European Affairs within the Directorate for Trade and Economic Affairs, is responsible for overseeing the general operations of the EEA Agreement. The Directorate of Executive and Legal Affairs provides crucial support on EEA legal matters and handles cases before the EFTA Court and the Court of Justice of the European Union. The Mission of Iceland to the European Union in Brussels also plays a significant role in coordinating EEA work.

The MFA's aim is to ensure that the necessary expertise and competencies are present in each relevant body. Certain EEA-related staff members are not part of the diplomatic rotation to ensure continuity. In recent years, there has been a focus on enhancing EEA knowledge and human resources within the administration. The MFA supports the work of other ministries on horizontal EEA issues and provides training within the administration.

Following up on the recommendations of the 2019 EEA report and other reviews the PMO has become more involved in EEA coordination. Since 2014 a representative of the PMO has chaired a Steering Group for EEA Affairs within the administration. This group focuses on improving processes, identifying key areas, and following up on proposals within the EU legislative process. The Permanent Secretaries of the PMO and the MFA jointly champion the Agreement within the administration. The PMO also has representation at the Icelandic Mission in Brussels.

As more EU acts require incorporation into the EEA Agreement and affect multiple ministries, plans are underway to establish an EEA Coordination Committee within the central administration. This committee will facilitate structured cooperation and take over the role of the existing Steering Group.

Regarding representation in Brussels, Alþingi, has expressed a desire to have its own representation connected to the European Parliament, but this has not yet materialized. The Association of Local Authorities in Iceland has a representative in Brussels, independent of the Icelandic Mission. Social partners primarily follow developments and secure their interests from Iceland and via European social partner organizations. The Association of Employers in Iceland has occasionally had representation in Brussels.

In recent years, several noteworthy reforms have been implemented in Iceland to strengthen the functioning of the EEA Agreement and enhance Iceland's participation within the cooperation. These reforms include:

- Adoption of Priority Lists: Starting in 2016, the Icelandic government began adopting Priority Lists of acts in the EU legislative process that should be in focus for the administration. This tool helps prioritize issues and ensures early engagement in the legislative process, which is crucial for a small administration. The work done to safeguard Iceland's interests in relation to acts on the Priority List is evaluated, and the results are published.

- Establishment of the EEA Database: In 2017, a centralised EEA Database was introduced to facilitate coordination and work within ministries, particularly regarding the incorporation of new acts. The Database also provides better overview and insight into EEA affairs for citizens and practitioners of EEA law. Efforts will continue to integrate the Database into the filing system of the central administration and explore further IT solutions.

- Reinforcement of the Mission of Iceland in Brussels: Over the past decades, the Mission of Iceland in Brussels has been strengthened, with all ministries now represented. This is important for monitoring and advocating Iceland's interests in EU policymaking and within the EEA cooperation. The Director of EEA Cooperation from the MFA ensures integration of the embassy's work with wider coordination and EEA efforts within the Icelandic administration. The Mission produces a biweekly newsletter on EEA current affairs distributed widely in Iceland and within the administration.

- Evaluation of Iceland's Participation in EU Comitology Committees and Expert Groups: In 2019, a survey was conducted to assess Iceland's participation in EU comitology committees and expert groups as outlined in the EEA Agreement. The survey identified a total of 649 committees and groups where Iceland had the opportunity to participate. Among these, there were 184 comitology committees and 465 expert groups. The preliminary findings indicated that Iceland was regularly or ad hoc participating in 64 comitology committees and 181 expert groups. Another survey is currently underway in consultation with relevant ministries to further prioritize Iceland's participation in these groups and committees based on necessity.

Iceland's participation in EU agencies has proven highly beneficial, as it brings the Icelandic Administration closer to EU policymaking and execution. This closer involvement enables Iceland to better safeguard its interests within the EU framework.

These ongoing reforms demonstrate Iceland's commitment to strengthening its participation in the EEA Agreement, improving coordination within the administration, and actively advocating for its interests within EU processes.

The implementation of EEA acts in Iceland has undergone improvements in recent years, although certain challenges remain. Here is an overview of the consultations, incorporation, and implementation processes:

- Consultations with Alþingi: The MFA delivers an annual report on the functioning of the EEA to Alþingi. Prior to incorporating acts into the EEA Agreement, Alþingi is consulted on all acts requiring legislative changes. The Foreign Affairs Committee provides opinions and may refer matters to relevant standing committees for further scrutiny. The Committee is also consulted on the Priority List for important EU legislative proposals.

- Bill to reinforce Protocol 35: In 2023, the foreign minister tabled a bill to reinforce the implementation of Protocol 35 to the EEA Agreement. The aim is to enhance the reliance of citizens and economic operators on the rights and obligations provided by the EEA Agreement, aligning implementation with Norway's approach.

- Procedures for incorporation and implementation: The EFTA procedures provide a uniform basis for the EEA/EFTA States, while national procedures may vary. Meeting deadlines and incorporating numerous acts can be challenging for a small administration. However, efforts have been made to reduce backlogs, particularly in the field of Financial Services, through joint efforts with the EEA/EFTA States.

- Timely implementation of EEA acts: Acts generally need to be translated into Icelandic before implementation, although certain exceptions apply. Recent efforts have been made to have acts already translated at the time of incorporation. Implementation of acts requiring legislative changes depends on parliamentary timelines and cycles, which can be influenced by elections or major. unforseen events like COVID-19.

- Reduction of implementation deficit: Iceland has managed to reduce its implementation deficit in recent years. As of November 2022, the deficit stood at 1% for directives and 3.7% for regulations, with a notable improvement from 5.5% in 2021 for regulations. Efforts are ongoing to further address the implementation deficit.

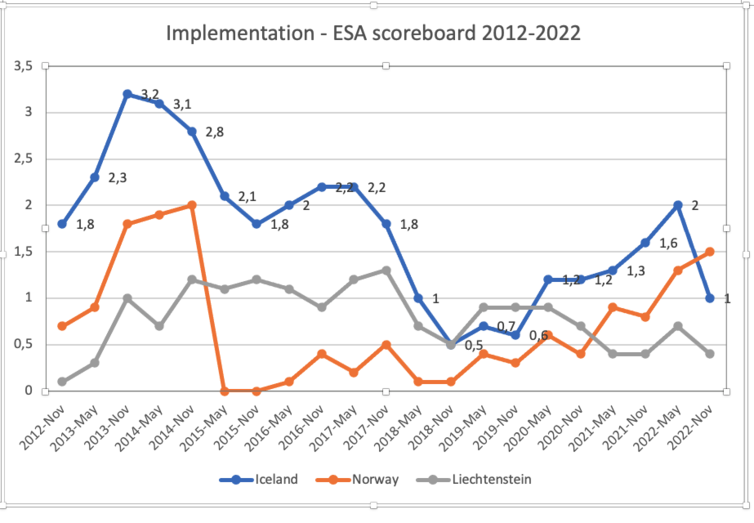

The implementation record of Iceland for directives from 2012 to 2022 can be seen in the provided chart.

Iceland ensures that legislative changes required by EU acts are implemented in accordance with constitutional requirements. The government has streamlined the process for lifting constitutional requirements by combining multiple resolutions into one motion in the Icelandic Parliament, Alþingi. Currently, there are 14 decisions under constitutional requirement in Iceland, with five of them from 2021, where the 6-month deadline for lifting has passed.

Efforts to reduce backlog and mitigate implementation deficits have included a range of strategic measures, such as:

- Temporarily bolstering ministries, especially in sectors experiencing significant backlog and implementation deficits, to ensure adequate resources. Key focal points have been the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Industries and Innovation (now Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries).

- Instituting parliamentary rules regarding the processing of EEA acts. These mandate that the implementation of EEA acts through legislation should occur via dedicated bills, and any additional provisions within those bills must be explicitly identified.

- Engaging in early consultations with the Foreign Affairs Committee of Alþingi concerning EEA Acts during the preliminary stages of the incorporation process.

- Enhancing the Translation Division of the MFA to guarantee the timely translation of EEA acts for implementation.

- Implementing regular oversight and maintaining consistent communication with the relevant ministries by the MFA.

- Establishing the EEA Database as a practical tool for ministries, thereby offering an improved overview for the MFA.

- Facilitating administrative cooperation on more intricate files to foster streamlined operations.

- Providing robust support to line ministries regarding questions of a horizontal or institutional nature, which includes addressing two-pillar issues and EEA relevance. This encompasses offering training courses.

- Amplifying awareness regarding the crucial importance of the timely incorporation and implementation of EEA acts to maintain homogeneity across the board.

The Brussels-based EFTA Secretariat serves a crucial role in ensuring the smooth incorporation of acts and operation of the EEA Agreement. This is accomplished through collaborative monitoring of backlogs and the establishment of priorities and timelines for the EFTA working groups. These groups, comprised of experts from EFTA member states, are dedicated to addressing specific issues or areas of cooperation. The Secretariat provides valuable support to these working groups, fortifying their operations and initiatives.

Incorporation procedures have been refined to enhance efficiency; in specific domains, simplified processes have been introduced to expedite the drafting of Joint Committee Decisions (JCDs). The EFTA Joint Committee, which oversees the management of the EEA Agreement, adjudicates these JCDs. These decisions are integral to the EEA Agreement, ensuring the seamless operation of the EEA internal market.

To enable informal dialogues with the EU Commission, occasional taskforces are organized. These are specifically formed to navigate through complex files, prioritize files, and address areas with considerable backlogs as Joint Committee Decisions are formulated within the EFTA working groups.

(The author expresses gratitude to Mr. Ingólfur Friðriksson, Deputy Director General, European Affairs, Directorate for External Trade and Economic Affairs, MFA, for his valuable assistance in gathering the data and information presented in this chapter.)

4. Present and Future relations of Iceland with the EU

The establishment of the European Economic Area (EEA) in the 1990s provided Iceland with enhanced access to the European market. This integration into the EEA has been crucial for Iceland's economy, allowing for the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people between Iceland and the EU member states.

However, ongoing debates and discussions regarding Iceland's membership in the EEA and future relations with the EU can be categorized into four main strands:

- Political Realm: The consensus among political parties regarding the EEA remains consistent with their viewpoint in 2007, acknowledging that adherence to the four freedoms outlined in the EEA Agreement is beneficial for Icelandic interests. While some parties are positive towards EU membership, others remain opposed.

- Business Community: The views of the business community are important, as they are directly impacted by the implementation of the EEA Agreement. The business community emphasizes the importance of access to markets abroad and the benefits of international trade cooperation for deregulation and modernization of the Icelandic economy.

- Free Movement and Scientific Cooperation: Iceland's participation in the free movement of people within the EEA has brought various benefits, including labour market flexibility, innovation, and cultural exchange. Additionally, participation in EU scientific programs, such as Horizon Europe, has facilitated research collaborations and advancements in various scientific fields.

- Legal Issues: Legal matters concerning Iceland's participation in the EEA and alignment with EU regulations and sanctions are also part of the ongoing discussions. Ensuring legislative changes comply with constitutional requirements and aligning with EU policies and foreign policy decisions are important considerations.

The core issue underlying these debates is how to guarantee access for Icelandic products and services to international markets. Iceland's participation in international trade cooperation, such as the EEA, has been essential in fostering economic growth, strengthening relations with allies, and maintaining economic sovereignty.

Historically, concerns have been raised about the potential impact of close alignment with larger market economies on Iceland's economy, independence, and living standards. However, membership in multinational market alliances, like the EEA, has provided Iceland with opportunities for trade cooperation and negotiating power with the EU.

In summary, Iceland's debates on the EEA membership and EU relations revolve around ensuring access to markets, maintaining economic sovereignty, and balancing the interests of different stakeholders, including political parties, the business community, and the scientific and research sectors.

In terms of foreign policy alignment, Iceland has consistently complied with EU sanctions, including those imposed on Russia and Belarus. Additionally, Iceland has generally aligned with other EU foreign policy statements when timely invitations to align have been received. This demonstrates Iceland's commitment to maintaining alignment with the EU in matters of foreign policy.

Politics

The EEA Agreement underwent extensive deliberations in Alþingi. Ultimately, 52.4% of parliamentarians voted in favour of the bill, 36.5% voted against it, and 11.1% abstained.

Opponents of the Agreement argued that it violated the Constitution and expressed concerns about the Icelandic economy's ability to withstand increased foreign competition and foreign capital influx. They believed the Agreement posed a significant threat to Icelandic sovereignty. At the time of adoption, one party, the People's Alliance, proposed a bilateral agreement on trade and cooperation between Iceland and the European Community as an alternative.

As described above the EEA Report of 2019 was written while Alþingi debated the EU's third energy package. The Icelandic discussions were prompted, in part, by the polemics in Norway regarding the EU's the package and the participation in ACER. If Alþingi rejected the package, the EEA/EFTA States would remain outside the cooperation concerning that aspect of EU energy market legislation.

It should be noted that comparing Iceland to Norway in terms of European energy cooperation is misleading, as Icelandic energy companies do not directly sell energy through undersea cables for transmission into the European energy grid. The example of Norway was likely used to criticize EU energy regulation and disparage the EEA more generally.

From the perspective of the Icelandic government, the third energy package represents a successive step towards further marketization of electricity generation and supply, building upon the frameworks established by the First and Second Energy Packages, and institutionalized through the Electricity Act in 2003 and 2008. This package encompassed stipulations concerning consumer rights and protection, access to electricity transmission and distribution networks, market transparency, and the segregation of energy generation and supply from transmission and distribution, all aimed at fostering competition, among other objectives.

During deliberations in the Alþingi, a legal stipulation was asserted, ensuring that any initiative to connect Iceland's electricity system with another country via a submarine cable connection would necessitate prior authorization from the parliament. Furthermore, a joint press statement from the Icelandic Minister for Foreign Affairs and the European Commissioner for Energy articulated: “Decisions regarding electricity interconnectors between Iceland and the EU's internal electricity market reside solely within the jurisdiction of Icelandic authorities.”

This debate generated a sense of distrust both within and outside the parliament, especially among members of the Independence Party. While the party backs EEA membership, it holds a significant position in shaping the outcome regarding opposition to the EEA or support for EU accession.

The lingering discomfort regarding the EEA collaboration, particularly within the Independence Party, stems mainly from apprehensions about its effect on Icelandic sovereignty. There is a group formed by certain party members with the slogan "Free Nation in a Free Country" that is critical not only of the EEA's influence on Icelandic society but also, for example, the adherence to COVID-related demands by the WHO.

It's worth noting that no Icelandic political party currently prioritizes leaving the EEA, except for those few who cautiously advocate for EU membership. Their primary argument revolves around Iceland's absence from the decision-making table where matters impacting the country's future are discussed. Another key point they raise is the vulnerability of the Icelandic krona, asserting that adopting the Euro would offer greater economic stability.

Those who hold a negative stance towards the EEA employ arguments that echo criticisms seen across Europe, emphasizing the transfer of too much authority to unelected Brussels bureaucrats who may appear hostile to the sovereignty of individual nation-states. They often cite specific issues, such as the third energy package or the implementation of protocol 35, to reinforce their position.

Both proponents of EU membership and EEA critics employ the argument that Iceland lacks direct influence at the bargaining table to advance their respective agendas. Their objectives are either to secure EU membership or to wield veto power over certain EU proposals.

For a government aiming to maintain a balanced and stable commitment to the EEA, it becomes imperative to establish a well-defined and effectively executed list of priorities when looking after Iceland's interest in the EU legislative process and the EEA incorporation process. Building strong connections with Alþingi and delivering timely and transparent information to the public are vital components of this strategy.

The current policy declaration of the three-party coalition consisting of the Independence Party, Left-Green Movement, and Progressive Party states: “Iceland's interests are best served outside the European Union. The Government will place increased emphasis on the implementation and development of the EEA Agreement in a manner that will secure Iceland's interests and sovereignty in co-operation and trade with other states.”

Regarding the opposition, it is worth mentioning that the Social Democratic Alliance, which favours the EEA, has reduced its focus on its EU membership stance under new leadership since 2022. While other parties also support the EEA, there are some, such as the Liberal Reform Party (Viðreisn), that advocate for EU membership. The Centre Party holds the most critical position towards both the EEA and EU.

Business Community

The business community is directly impacted by the implementation of the EEA Agreement.

In negotiations in the decision-making process to determine how EU legal acts apply to the EEA/EFTA States the terms "adaptation" and "derogation" are important, with adaptation referring to specific situations accepted during the implementation of decisions and derogation making it possible for a particular state not to incorporate a certain legal act.

A doctoral dissertation conducted by Christian Frommelt, a scholar hailing from Liechtenstein, offers valuable insights into the incorporation of EU acts into the EEA Agreement. Frommelt's research revealed that between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2015, approximately 86.7% of EEA relevant acts were incorporated into the EEA Agreement without any modifications. Only 6.1% of the adaptations specific to the EEA were purely technical in nature, while 7.2% of the EEA relevant acts incorporated into the EEA Agreement required substantial modifications. The number of adaptations negotiated by the EEA/EFTA States has shown a decline from 1999 to 2009.

Iceland has engaged in negotiations and obtained adaptations in several areas to accommodate its specific circumstances within the EEA. These adaptations include:

- Importation of live animals: Iceland has negotiated adaptations regarding the importation of live animals, likely to address the unique conditions and requirements related to animal health and welfare.

- Aviation security: Due to Iceland's specific geographical situation, adaptations have been made regarding aviation security. Domestic air services within Iceland are exempt from certain provisions of the EU regulation on aviation security, which primarily applies to international flights.

- Safety requirements for fishing vessels: Adaptations have been negotiated concerning safety requirements on board fishing vessels. These adaptations likely aim to address the specific needs and challenges of the fishing industry in Iceland.

- Energy performance of buildings: Iceland has negotiated adaptations regarding energy performance requirements for buildings. These adaptations may reflect the country's specific climate conditions and the need for energy-efficient buildings.

- Daylight Savings Time: Adaptations have been negotiated regarding Daylight Savings Time. Iceland may have specific considerations related to time changes and their impact on various aspects of society.

- Electricity market: Adaptations have been made in the electricity market to accommodate Iceland's specific circumstances. These adaptations may reflect the country's abundant renewable energy resources and their utilization in the electricity sector.

- Environmental matters: Iceland has negotiated adaptations in environmental matters, likely to address specific environmental challenges and conservation efforts within the country.

Additionally, Iceland has implemented a permanent derogation that prohibits non-nationals and non-resident nationals from investing in fishing vessels and fish processing. This derogation may aim to protect and prioritize the involvement of Icelandic nationals and residents in the fishing industry, which is significant to the country's economy and society.

These adaptations and derogations demonstrate Iceland's efforts to tailor certain regulations and policies to its unique circumstances while participating in the EEA.

Iceland is committed to achieving climate goals, but it has also sought adaptations in greenhouse gas and aviation emissions discussions to recognize its unique geographical position. Rules applicable to overseas flights, if they create an unfair playing field for operators, could harm connectivity, air transportation over the North Atlantic, isolate the country, and impact tourism.

"Gold plating" in the context of Iceland's implementation of EEA regulations refers to the practice of adding stricter or additional regulations beyond what is required by the EEA agreements. This can result in regulatory divergence and impose additional burdens on businesses operating in Iceland.

A study initiated by the Prime Minister's Office in 2016 suggested that up to one-third of EU directives implemented into Icelandic legislative framework were subject to gold plating. This means that Iceland went beyond the minimum standards set by the EEA agreements and added extra requirements or conditions to certain European legislation.

The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce highlighted the impact of gold plating in July 2023, specifically in relation to the implementation of EU rules on the disclosure of non-financial information by corporations (EU NFRD rules). The decision to include companies with 250 employees instead of the EU-required minimum of 500 resulted in additional costs for Icelandic companies. The Chamber estimated that this decision had cost Icelandic companies up to 10 billion ISK since 2016, affecting a larger number of companies (268) compared to the original requirement (35).

Gold plating can lead to increased costs, administrative complexities, and potential barriers to trade and investment. It may create a negative perception of the EEA, although the root cause lies in the decisions made by Icelandic authorities and the regulatory framework in the country.

Towards the end of January 2024, the Icelandic Foreign Minister appointed a working group to develop a plan to address gold-plating. The Minister stressed that it should be evident when EEA regulations are implemented whether they are required by EEA membership or are homegrown rules. The working group is tasked with analyzing implemented texts and establishing necessary benchmarks to enhance practices.

For the Icelandic business sector, it is necessary to facilitate enterprises with unencumbered access to EEA-markets through the elimination of quantitative restrictions and trade barriers, alongside reduced customs duties. Furthermore, the EEA Agreement grants and dictates rights and duties to individuals and legal entities across various domains where EU laws are amalgamated into the Agreement. Individuals can transparently seek such rights against the state, especially when compared to other international accords. For example, state courts recognize liability for damages in instances where individuals or legal entities incur losses due to improper or non-implementation of acts integrated into the EEA Agreement in national law.

A degree of ambiguity has lingered regarding the adequacy of incorporating Protocol 35 into Icelandic law. This has been underscored by EEA law scholars and manifested in the ESA's ongoing infringement proceedings, exemplified in a formal notice to Iceland in December 2017 and a reasoned opinion in September 2020, both highlighting Iceland's non-compliance with implementing Protocol 35. Should the process advance, the ESA has signalled that the subsequent step entails initiating an infringement procedure at the EFTA court. The objective of this action would be to secure acknowledgment from the Court of Iceland's non-fulfilment of its obligations under the EEA Agreement by inadequately implementing Protocol 35.

Opting to pre-emptively address this matter prior to EFTA court adjudication, the Minister for Foreign Affairs proposed a bill, introducing amendments to Article 4 of the Act on the EEA Agreement, aiming to assure comprehensive implementation of Protocol 35 in Icelandic law. The ultimate intention is to enable natural and legal persons to fully exercise their rights under the EEA Agreement, and to protect the Agreement by removing any ambiguity regarding Iceland's adherence to international obligations under the Agreement.

The bill, introduced in late March 2023, did not progress through parliamentary stages before Alþingi's summer recess and is planned to be reintroduced in the autumn of 2023. The parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee largely expressed approval in their comments. Outside of parliament, critics arguing from a sovereignty perspective assert that Protocol 35 concedes excessive power to the EU to intervene.

It is the Foreign Minister´s intention to re-introduce the bill regarding Protocol 35 at the 2024 spring session of the Althingi.

It's crucial to note that this bill does not modify Iceland's obligations under international law but pertains to its internal implementation. Scholars have suggested that Article 2 of Act No. 209/1992 (EØS-loven) might serve as a pertinent model to emulate in this context.

(Source: Dr. Margrét Einarsdóttir, Stefán Már Stefánsson: "Beiting innlendra EES-reglna í íslenskum rétti í ljósi bókunar 35; Hæstiréttur í 100 ár – ritgerðir," 2020.)

Free movement – scientific cooperation

Iceland's participation in the free movement of people as part of the EEA cooperation has yielded significant benefits across various domains. Economically, it has contributed to a more flexible and versatile labour market, innovation, and competitiveness. Socially and culturally, it has enriched Icelandic society, fostering diversity, intercultural understanding, and tolerance. Demographically, it has addressed population challenges by attracting skilled workers and contributing to population growth. Additionally, the reciprocal free movement of people has facilitated tourism, cultural exchange, and educational opportunities, strengthening Iceland's ties with other EEA member states. Overall, Iceland has gained extensively from its involvement in the free movement of people, which has been crucial in shaping its economic, social, and cultural landscape.

It is important to note that the free movement of people also brings challenges that need to be addressed. For instance, managing labour market dynamics, ensuring fair competition, and integrating migrants into the Icelandic society requires effective policies and adequate resources. Addressing challenges resulting from the need of the domestic labour market and free movement of people is an ongoing task for Icelandic authorities.

Iceland's participation in the EU Framework Programmes for Research and Innovation has yielded numerous benefits for the country. Firstly, it has provided Icelandic researchers and institutions access to a wider network of European scientists, fostering collaborations and knowledge exchange. This has led to advancements in various scientific fields, including environmental research, renewable energy, geology, and marine sciences. Additionally, Iceland's participation has facilitated access to funding opportunities for research projects, enabling the country to further develop its scientific capabilities. Furthermore, it has enhanced Iceland's visibility and reputation in the international scientific community, attracting more research partnerships and opportunities for scientific innovation. Overall, Iceland's involvement in EU scientific programs has bolstered its research capacity and contributed to its scientific and technological progress.

Iceland's participation in the Erasmus program has yielded a wide range of benefits. It has expanded educational opportunities, fostered cultural exchange, strengthened networks and partnerships, boosted the economy, enhanced Iceland's international image, and contributed to personal and professional development. The program has played a significant role in shaping Iceland's education system, promoting internationalization, and cultivating a global outlook among its students, educators, and institutions.

Legal issues

The Icelandic Constitution does not contain provisions allowing for the transfer of powers to international organizations. According to Article 2 of the Constitution, legislative power is jointly exercised by the President of Iceland and Alþingi, and neither of them can be replaced in adopting legislation applicable in Iceland.

Based on legal advice, the majority of Alþingi concluded that the provisions of the EEA Agreement, its protocols, or annexes did not have direct legal effect on Icelandic citizens unless Icelandic constitutional rules were fulfilled. Each member state had veto power in the EEA Joint Committee, and new rules had to be adopted by parliaments or approved by governments in each member state.

The institutional setup of the two-pillar system in the EEA Agreement was a key focus of the debate, as concerns were raised about the potential transfer of powers to the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) and the EFTA Court, which might not be compatible with the Icelandic Constitution.

It was argued that the EEA Agreement established a new legal order and set the foundation for new rules governing the participating states in the areas covered by the agreement. The surveillance and court systems were designed to monitor compliance with those rules. Participation in this cooperation did not entail the transfer of state powers, as the decision-making powers granted to EFTA and EC institutions through the EEA Agreement did not originally belong to the Icelandic state.

The focus primarily centred on the executive powers granted to the European Surveillance Authority (ESA), particularly concerning competition issues that impacted trade among the contracting parties. These powers had limited applicability and did not overly burden individuals and entities in Iceland. The review powers of the EFTA Court were similarly characterized. Accordingly, it was argued that EEA membership did not violate the Constitution.

It was also noted that Iceland would appoint representatives to the ESA College and the EFTA Court as part of its participation in the EEA Agreement.

From 1992 to 2019, 18 official legal opinions were provided on constitutional questions concerning the EEA and Schengen issues, as well as Alþingi's position on these matters. None of these issues were considered unconstitutional. Here is a list of 12 such issues:

| 1992 | Ratification and implementation of the EEA Agreement |

| 1999 | Schengen Cooperation |

| 2004 | Enforcement of Competition rules |

| 2011 | European Aviation Safety Agency |

| 2012-2014 | European Supervisory Authorities – ESAs (Financial Services) |

| 2012 | Emission Trading Scheme – common registry for allowances |

| 2012 | European Medicinal Agency |

| 2015 | Surveillance of State Aid |

| 2016 | Competencies relating to Ship Inspection |

| 2017 | General Data Protection Regulation |

| 2019 | Third Energy Package |

| 2023 | Implementation of Protocol 35 |

As stated before, the 2019 EEA report pointed out that the ongoing constitutional debate regarding EEA membership must be concluded, either by recognizing the constitutional status of this membership, like other unwritten constitutional rules, or by amending the Constitution to explicitly address Iceland's membership in the Agreement.

5. Alternatives to EEA Membership

As of 1 January 2022, the EU Commission´s Secretariat-General is responsible for coordinating the EEA incorporation process on behalf of the European Union. Previously, the European External Action Service (EEAS), was responsible for handling the EEA Agreement on the EU side.

Under the responsibility of the EEAS Iceland often felt that the EEA was on the side line with small official focus and competing with much more pressing issues. This change with the internal transfer of responsibilities and the EU seems now both more active and demanding when it comes to the running of EEA Agreement.

Vice-President of the Commission Maroš Šefčovič responsible for Interinstitutional Relations and Foresight said in a speech in Iceland on October 20, 2022, that the EEA Agreement promoted prosperity, innovation, and competitiveness, while ensuring the highest social, consumer and environmental standards. It guaranteed equal treatment and legal certainty for Europeans and European businesses alike: „I firmly believe that this effective model for cooperation suits the needs of both the EU and the three EEA/EFTA states. “

He also stated that the existing elements of the EEA Agreement continued to be able to provide solutions to emerging needs and common interests, as had been the case for years. The fact that the Agreement had not needed to be changed for almost 30 years underlined how well it was designed. And the parties to the Agreement had „the flexibility to look at other forms of cooperation when and where they might be needed “.

As this speech confirmed there is no pressure from the EU side to change the EEA arrangement, from their point of view it works well and should not be tampered with. In the unlikely situation that Iceland might consider choosing a different international trade framework – apart from joining the EU – it would be faced with these possibilities:

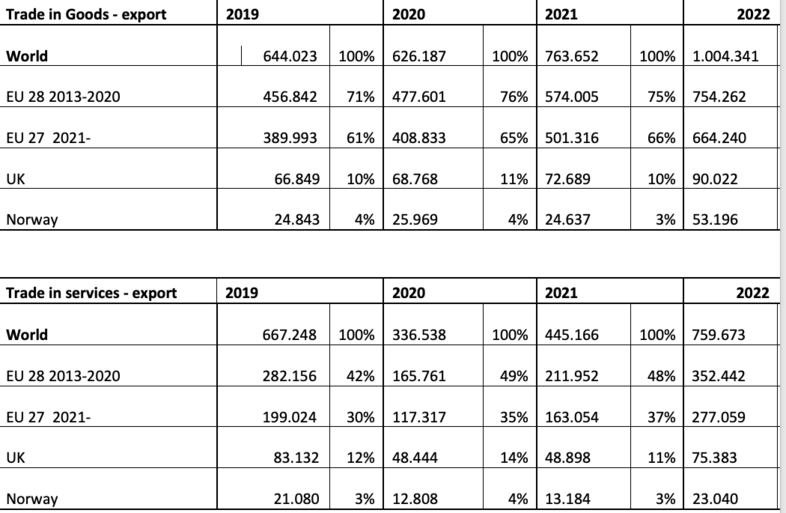

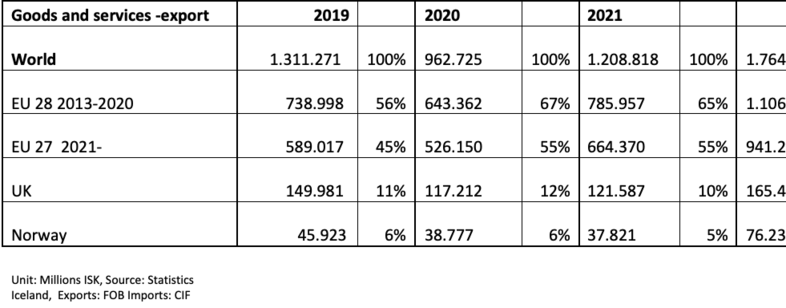

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs): Iceland could pursue free trade agreements with countries outside the EEA. FTAs aim to reduce trade barriers and promote economic integration. For example, Iceland has already signed a free trade agreement with China. However, given more than 55% of trade in goods and services is with the EU (more than 65% considering goods only) and barriers to key markets for goods are already relatively low (because of FTAs or liberalisation based on GATT), this does not really provide a viable alternative.

In August 2022 Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska introduced along with Independent Senator Angus King from Maine a bill in the U.S. Senate focused on increasing national security, shipping, and trade in the Arctic, including a resolution calling for a free trade agreement (FTA) with Iceland. Murkowski noted that Iceland had signed a trade deal with China in 2013 and said an FTA would “mean a great deal to Iceland and it doesn't take much from us.” Her aim was to take measures to help protect U.S. Arctic interests, project U.S. capabilities in the High North, leverage U.S. strategic location, and deepen relations with Arctic allies.

From 2017 to 2021 the Icelandic foreign minister often raised the issue of a bilateral FTA in discussions with high U.S. officials. Some preliminary talks took place at a lower level. This is more of a political topic than a practical one – so far at least.

European Free Trade Association (EFTA): Iceland, as a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), would remain part of the association alongside Switzerland, Norway, and Liechtenstein. However, if Iceland were to exit the EEA, its EFTA membership alone would not ensure continued access to the European single market while providing greater policy flexibility.

In terms of its position, Iceland would be in a similar situation as Switzerland, but without the same leverage that Switzerland has had in forging bilateral agreements with the EU. The current stalemate in EU-Swiss relations makes is highly unlikely that the EU would be inclined to pursue any customized bilateral arrangement with Iceland to cater to its specific needs.

Furthermore, pursuing custom-made agreements with the EU, as seen in the Brexit process, may not be very appealing or advantageous for Iceland.

The main conclusion is: The past three decades have demonstrated the benefits and success of Iceland's EEA membership, leading to significant economic prosperity. Any changes to this arrangement would likely cause major disruptions to the economy and in Icelandic politics, and the arguments in favour of such changes are significantly weaker compared to the strong reasons supporting the continuation of EEA membership.

Trade with key European partners:.

Numbers on free movement/labor migration.

The authorities lack exhaustive statistics regarding individuals utilizing free movement for work or other purposes at a specific moment. Nevertheless, immigration is notably high per capita in Iceland, as validated by Eurostat figures. For additional details, refer to Migration and migrant population statistics - Statistics Explained (europa.eu).

Predominantly, people are relocating to Iceland for employment opportunities, driven by a considerable staff shortage experienced in recent years, especially within the tourism and construction sectors.

| EEA nationals | Year | |

| 2021 | 2022 | |

| Net immigration | 2.477 | 5.522 |

| Immigration | 6.163 | 9.637 |

| Emigration | 3.686 | 4.115 |

Source: Statistics Iceland, change in legal domicile.

The substantial inflows and outflows for residence attest to the dynamic nature of free movement to and from Iceland.

A significant number of individuals also reside in Iceland for short work stays (less than 6 months), availing themselves of a simplified registration process for income tax purposes. While data on inflows are relatively straightforward to acquire, monitoring outflows has proven more difficult, given the lack of similar incentives for people to deregister upon departure.

In 2022, immigrants comprised approximately 20% of the workforce, maintaining a level that has been stable in recent years (Source: Statistics Iceland). Most of these immigrants are EEA nationals. Furthermore, the number of officially registered job seekers remains low, largely attributed to the elevated employment level.

Sources/references:

Skýrsla starfshóps um EES-samstarfið (stjornarradid.is) – page 290 to 301